The 1891 shearers’ strike is just one consequence of the many pressures applied to the wool industry which has been in decline since Hargreave’s invention of the spinning jenny. some of these pressures include:

- the mechanisation of weaving through the use of power looms,

- the mechanisation of shearing through the introduction of powered hand pieces and the introduction of wide combs,

- the decline in the demand for wool to cloth armies against severe winters,

- the introduction of alternative clothes made of cotton and synthetic fibres and

- the periodic government regulations applicable to the selling of wool.

The 1891 shearers’ strike is not a unique response by those least able to respond to the contraction of the wool industry. More widely, not only has my immediate paternal family experienced changes in the wool industry but, on reflection, so have some of my more distant ancestors.

Nottingham was one of the worst slum areas in England – particularly at the time of the depression in the early 1800s. Work in the weaving industry was uncertain, the more so when mill owners introduced mechanised weaving and the use of wide frameworks. Nottingham was the centre of riots by weavers directed at the mill owners. It is easy to imagine that 20-year-old George Watts, without work in Nottingham, would have participated. The ring leaders were sentenced and transported to Tasmania. George avoided transportation by enlisting in the 19th Foot Regiment. He spent the next twenty years in Ceylon and returned home to be discharged suffering from exhaustion. Maybe Tasmania would have been a better option.

Simon Uncles Salter, a little younger than George Watts, was a clothier in Wiltshire, as was his father before him.

A clothier is a maker or seller of woollen cloth or clothing. In particular, a clothier treats cloth after weaving.

In a better position than George Watts, Simon Uncles Salter was able to take advantage of the changes occurring in the wool industry. When Francis Hill, owner of a clothing factory in Malmsbury, Wiltshire, died litigation delayed the finalisation of his estate for some years. Eventually, Simon Uncles, in conjunction with his brother Isaac, was able to purchase Hill’s factory in which they installed a steam engine in 1833. In his later years Simon Uncles Salter sometimes described himself, in addition to being a clothier, as a wool stapler.

A wool stapler is a dealer in wool. The wool stapler buys wool from the producer, sorts and grades it, and sells it on to manufacturers. This is done by assessing parts of a fleece, the wool staples. A wool staple is a naturally formed cluster or lock of wool fibres.

Simon Uncles may have still accepted cloth from weavers for further processing. Now with a factory requiring wool (and therefore bypassing the weavers), he may have had control over the fleeces he accepted. For that he needed to be a wool stapler as well as a clothier.

Not long after Simon Uncles Salter commenced working his Malmsbury, Wiltshire factory William Learmonth went broke in the 1837 Tasmanian depression. With Victoria opening up there was a rush to obtain land suitable for large flocks of sheep. A family story is that William helped Thomas and Somerville Learmonth bring some of their flocks across Bass Strait to Victoria.

The Australian wool industry was a vastly different industry to the weaving industry in Wiltshire. The flocks were large but there was difficulty in finding skilled labour. Particularly at shearing time.

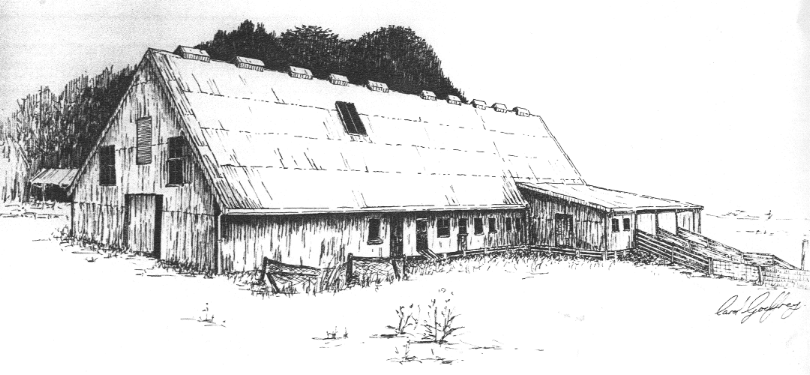

Before the 1891 shearers’ strike, Pearson, managing Dunmore, was able to start shearing at the beginning of November 1888 with a full board of 18 shearers. They were non-union men and Pearson paid them 15 shillings per hundred (whereas Samuel Baulch on next door Glengleeson had advertised for shearers at 12 shillings the year before).

some years following the 1891 shearers’ strike, Samuel Baulch, now at Dunmore, lost a costly court case. Partly because he refused to sign the shearers’ award agreements and partly due to a disagreement over whether the sheep were too wet to be shorn. The case shows that the owner, Samuel Baulch, ran the shed with his sons Walter and Bert classing the clip.

A wool classer is a person trained to produce uniform and predictable lines of categories of wool.

Running the shed changed 1954, if not before. That year a contractor was used to run the shed. The contractor hired the shearers and the shed hands. The shearers hired their cook and the owner engaged the wool classer. The difference between a wool stapler and a wool classer is that a wool stapler, such as Simon Uncles Salter, takes the risk in working for themselves. A wool classer removes that risk by working for someone else.

Political factors seem to bedevil the wool industry. There was a scheme during World War I to help through the disruption of supply to Britain. This was continued post war by the British Australian Wool Realisation Scheme. And followed up by reserve or floor price schemes introduced in the 1950s and the 1970s – each ended with equally disastrous results.

The 1891 shearers’ strike is one of many ways in which the decline of the wool industry has manifest itself. Riots, strikes and government schemes. Each have risen out of the inherent ability of the wool industry to respond appropriately to a changing and declining industry.

2 responses to “Wool staplers and wool classers”

Patsy,

My great x 3 grandfather, George Mackillop, lived next door to Thomas Learmonth for a time in Davey Street, Hobart. George and Thomas were also involved in some business enterprises together, including establishing sheep stations in Victoria.

Vicki

It’s a small world isn’t it Vicki. I know the name Mackillop from my time at school in Geelong. The Learmonths are one of the difficulties in my family tree. I remember going to a reunion where there were many Learmonths but how we are connected has been difficult to prove. It’s interesting that Thomas from Hobart came across Bass Strait to Melbourne but William came across from Launceston to Portland. It just shows how fast Victoria was settled. I just remember Rex Learmonth’s advice to me. He said first (of some other Learmonths) that it couldn’t be proved they belonged in my family tree. Then he thought for a moment and said that no one could prove categorically that they didn’t belong there. Whatever. The real joy, as in so much family history, was in meeting them all.