When some of us started researching our family history we were advised to start with ourselves, then confirm our links to our parents, grandparents and so on up our family tree.

Based on our family stories, photographs and the written records we had we developed our research plan, one that was often focused on looking for more information about a favourite ancestor.

In doing so we used a variety of sources.

Now we have another source to add to our toolbox – DNA – and just as we planned our traditional family research plan so too can we plan our DNA research plan.

Just as in the past we scraped and saved to purchase the next birth, marriage or death certificate so too we should be saving up to purchase the next DNA test in our DNA research plan.

Not to have a DNA plan leaves us open to being flooded with hundreds of supposed DNA matches that in general have little, if any, application to our DNA research plan. We are looking for specific matches – those with other researchers who have ancestors, or an ancestor, in common with ourselves.

The first step in our DNA research plan is to avoid those bright shiny objects that pass across our eyes and distract us.

The first bright shiny object is DNA advice provided by the medical profession. In our role as family historians we are not entitled to provide medical advice. Consequently, the DNA we use for our family history research is quite separate from that used for medical purposes.

The second beguiling object that floats across our eyes is DNA used for anthropological purposes.

For example, it has been exciting to read the research that found evidence of human occupation in northern Australia by 65,000 years ago (see Chris Clarkson et al “Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago” Nature 547 306-310 (20 July 2017).

But do such discoveries help us conquer our own brick walls? The discovery in northern Australia was dated by reference to the fluorescence in the sand in which the discovery was made. Where is the link from our DNA today back to DNA of 65,000 years ago.

However, what is important to note about such discoveries is that they are made at a point in time.

When we think about our own ethnicity are we looking at one point in time?

When I look at myself:

My Parents were born in Australia. Is my ethnicity 100% Australian?

Six of my great grandparents were born in Australia. Two in England. Is my ethnicity 25% English?

Most of my second great grandparents were born in England. Does this make my ethnicity 81% English? It certainly doesn’t account for my Irish fourth great grandfather, John Bourke Ryan.

I have followed our paper family tree up through the branches for this example.

With respect to DNA we receive half our DNA from our father and half our DNA from our mother. But which half do we receive? And which half, as displayed in our family tree did they receive from their parents? And which half did they receive from their parents? And so on. Why, then, do we expect our ethnicity to be precisely the same as that of our siblings when there is doubt about what was received from which grandparent in the first place?

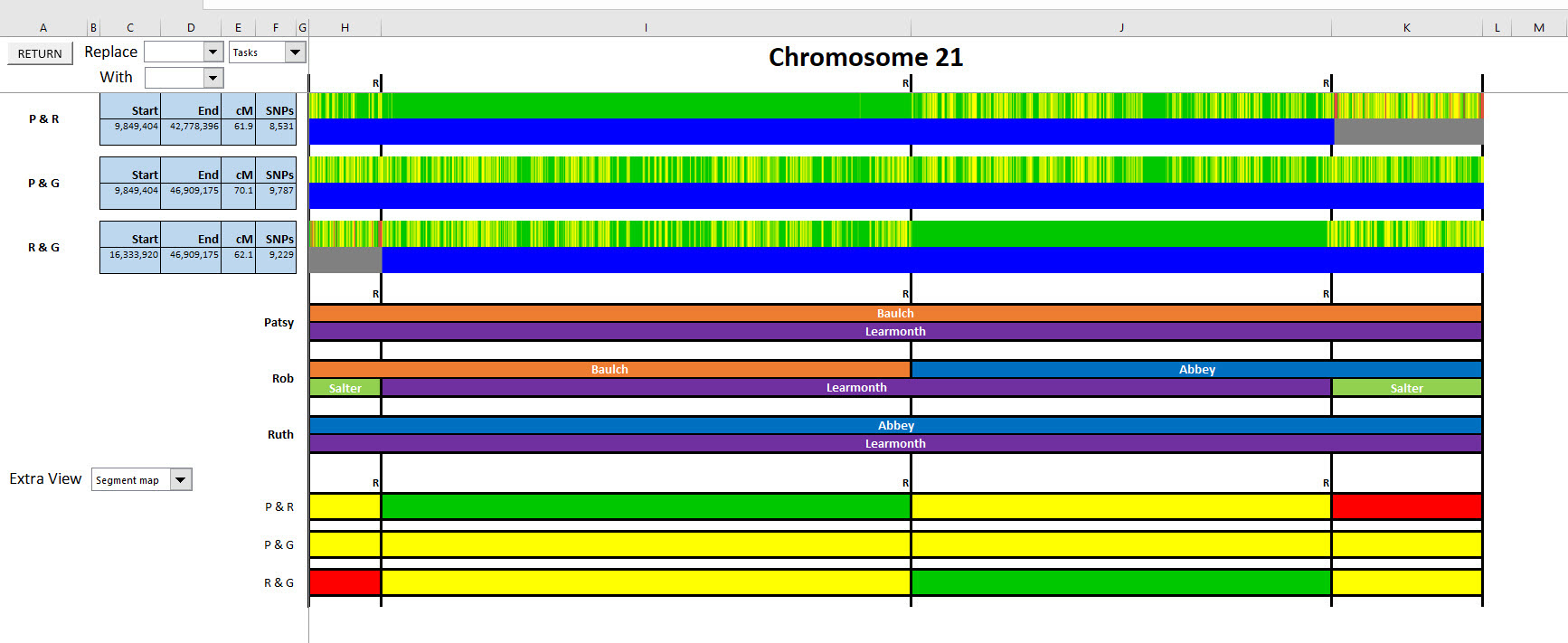

or example, on Chromosome 21 all my maternal DNA came from my maternal grandfather Learmonth. My sister also received all her maternal DNA from our grandfather Learmonth. While our brother also received most of his maternal DNA from our maternal grandfather Learmonth some of his maternal DNA came from our maternal grandmother Learmonth.

All my paternal DNA came from my paternal grandfather Baulch whereas my sister’s paternal DNA came from our grandmother Abbey. Our brother’s paternal DNA originally came about half from our paternal grandfather Baulch and about half from our paternal grandmother Abbey.

This simple example shows quite clearly that we each are unique. While receiving half our DNA from our father and half from our mother what we received that came from each of our grandparents may be very different. If we each calculate our proportion of DNA we get from each of our grandparents the answer is not the same for any two of us. Even at the grandparent level our ethnicity is different. Each of us is, after all, unique.

So why do we expect our ethnicity to be the same?

If we are using DNA as a source for family history purposes we should confine our family history research to the DNA that is used for genetic genealogy or family history purposes.

Results based on DNA used for medical purposes are given for medical reasons. Results based on DNA with ancient origins are for anthropological purposes.

We family historians have our own little sections of DNA that we use for family history purposes.

This doesn’t mean we can’t put our anthropological hat on now and then and tell a good story about our ancient origins. However, there is not necessarily a link between our ancient origins and our family stories of very recent times.

Where am I going to be:

28 July – 7 August 2017 – Unlock the Past Cruise – Papua New Guinea – to see where my uncle and father-in-law were in WWII

19 August 2017 – presenting “Using DNA to solve genealogical puzzles” at the Researching Abroad: British isles & European ancestors – Melbourne (find out more here)

11 November 2017 – presenting a half day session “DNA for family historians” for the Genealogical Society of Victoria (find out more here)

and when I get back from just cruising around the GSV will be taking bookings for DNA consultations (more here) . I expect to concentrate on autosomal DNA tests and I shall only be available on Fridays.

Hope to see you somewhere.